March 1970: Mercedes-Benz presents the C 111-II

- A four-rotor Wankel engine with an output of 257 kW produces top speed of 300 km/h

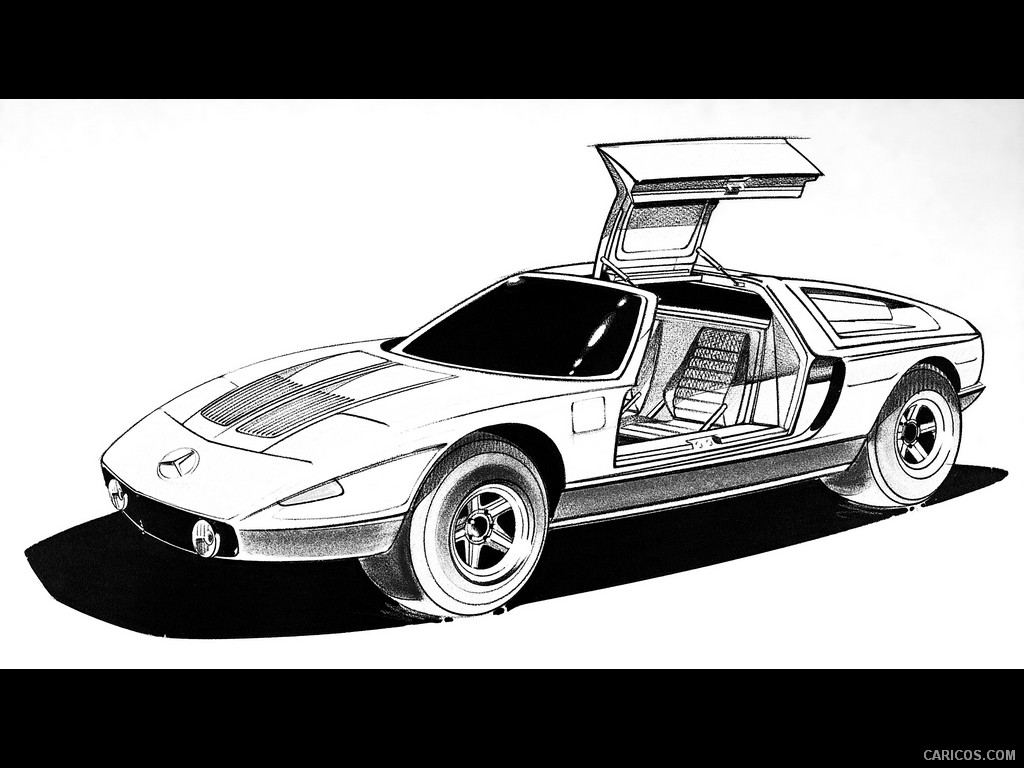

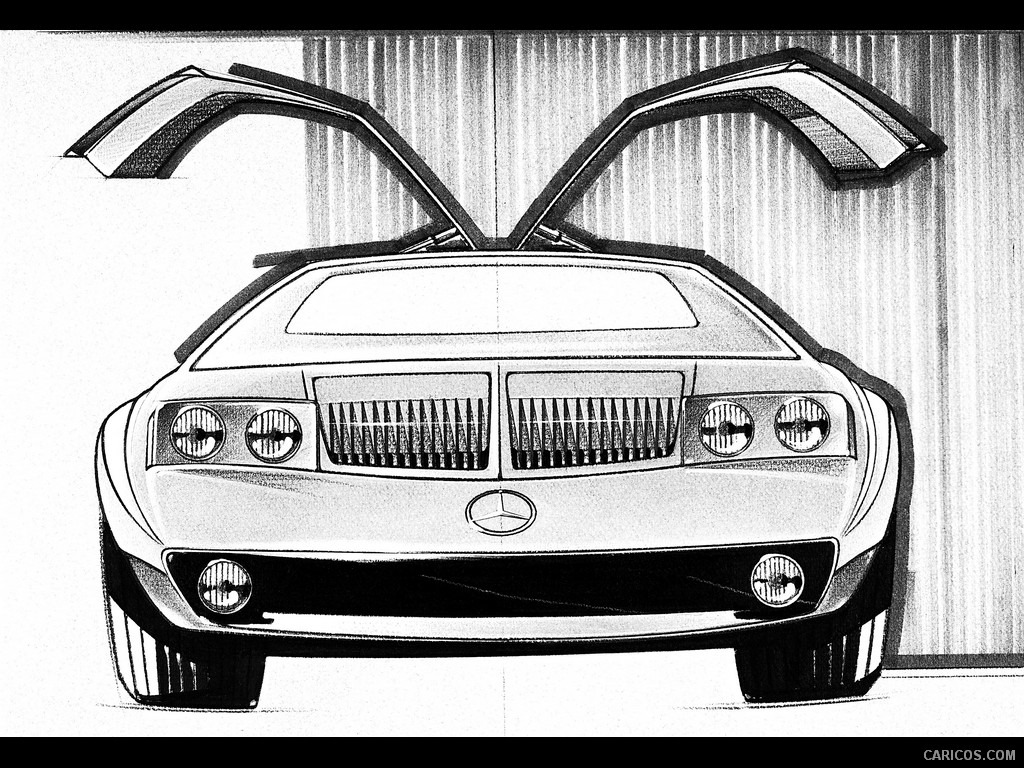

- An integrated concept – including engine, gullwing doors and interior design

- Highly innovative supersports car serves as test vehicle for series components

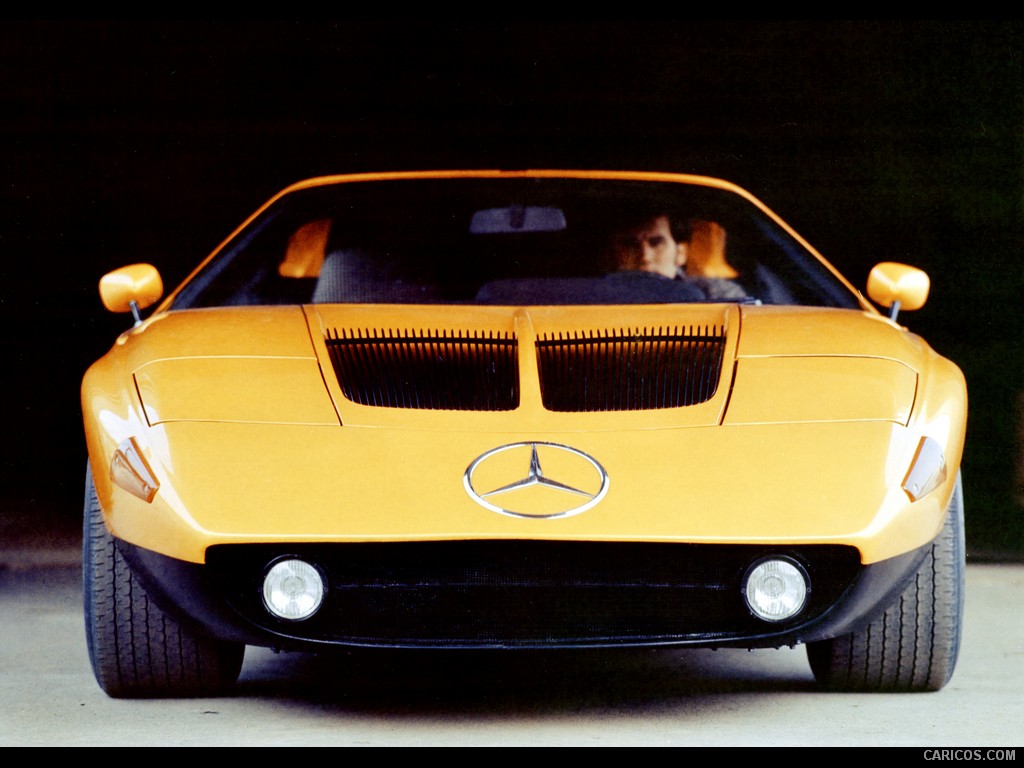

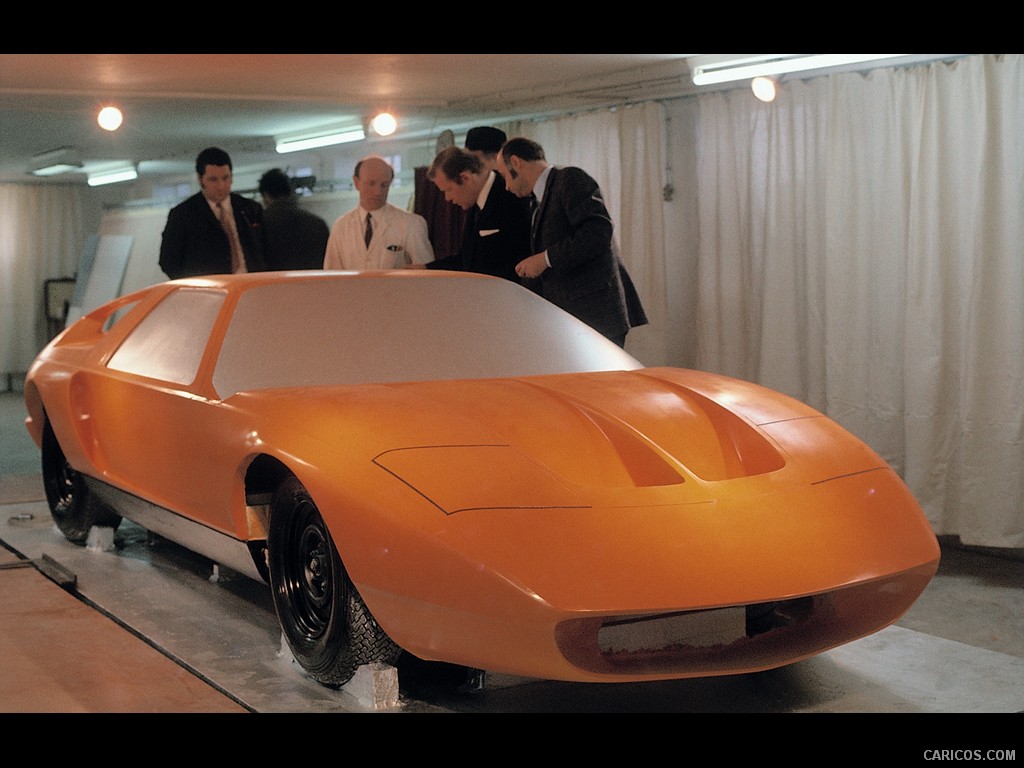

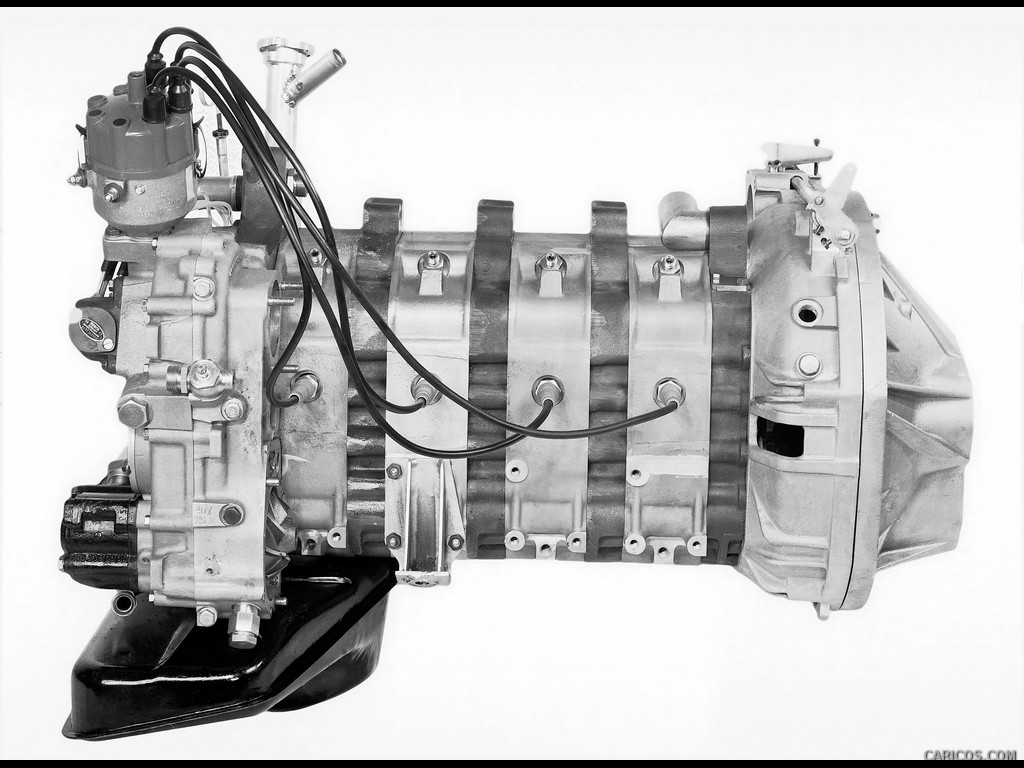

Stuttgart - When Mercedes-Benz introduced the C 111-II at the Geneva Motor Show in March 1970 it was the stuff of dreams: breathtaking body design, innovative materials and pioneering technology – not to mention top-level performance. An advance development of the study that had been equipped with a three-rotor Wankel engine and presented at the 1969 International Motor Show (IAA) in Frankfurt am Main, this version made its Geneva debut boasting a four-rotor Wankel engine developing up to 257 kW. The engine, a DB M950 KE409 model, had 600 cubic centimetres of volume per rotary piston and was the most advanced of the rotary piston engines developed at Mercedes-Benz. The engine transmitted its power to the rear wheels via a five-speed transmission, accelerated the C 111-II from a standing start to 100 km/h in 4.8 seconds and gave a top speed of 300 km/h.

In this version of the supersports car, painted an orange-red colour known as “Weißherbst”, the engineers succeeded in finding the perfect set-up for the mid-engined coupé with its distinctive gullwing doors. For in addition to a new engine, the C 111-II also boasted a modified body. As it appeared in Geneva, the car was much more than just a test vehicle for the innovative drive concept developed by Felix Wankel. Since the launch of the project in December 1967 Mercedes-Benz had developed a top-class supersports car with the wherewithal to fill the gap left by the Mercedes-Benz 300 SL (W 198 series). The enthusiastic response from visitors to the Geneva Motor Show confirmed this view. Orders were received even before the Stuttgart company had set a price for the new gullwing – many offering downpayments or blank cheques.

One improvement over the C 111-I was the new model’s improved aerodynamic efficiency: the drag coefficient of cd=0.325 was exceptionally low for the period. At the same time, driver visibility was improved. With the modified body and new Wankel engine, which now developed torque of 40 mkg (392 Newton metres), no contemporary road-going supersports car was a match for the C 111-II.

And yet Mercedes-Benz decided against series production. “The Wankel engine was not yet mature enough to be handed over to customers in line with company standards,” said Dr. Hans Liebold in the year 2000, the man who had been responsible for developing the C 111, from the first Wankel study right up to the later record-breaking cars with reciprocating piston engine. Moreover, increasingly stringent emissions regulations in the United States of America argued against the introduction of the rotary piston engine, for although it had typical fuel consumption figures for the period (“an average of 20 litres/100 km”, according to an issue of the magazine auto motor und sport dated 11 April 1970), emissions values were distinctly on the high side. A short time later, the oil crisis put an end to all hopeful speculation regarding the coupé’s market launch.

By this time the development department at Mercedes-Benz had largely got to grips with the engineering design problems of the rotary piston principle, particularly in terms of engine mechanics. But the relatively poor efficiency of the Wankel engine, which resulted from the elongated, variable combustion chambers of the rotary piston principle, could not be circumvented by technical modifications. The problem was simply inherent in the design: in a Wankel engine, the fuel burns in the space between the convex side of the rotary piston and the concave wall of the piston housing, rather than in the cylindrical combustion chamber of a reciprocating-piston engine. The variable and less than compact combustion chambers of the Wankel engine were responsible for poor thermodynamic fuel economy compared with a reciprocating-piston engine, resulting in significantly higher fuel consumption for the same output.

On the other hand, the engine had the advantages of a highly compact design and quietness even – while being driven for sports performance. In November 1969 Ron Wakefield also discussed the C 111 in the trade magazine Road & Track: “During my first ride I was immediately struck by the quietness of the power unit inside the car. It was far quieter than, say, a 12-cyl. [Lamborghini] Miura.”

In retrospect, Dr. Kurt Obländer, head of engine testing for the C 111 project, described the Wankel engine as follows: “Our four-rotor engine with gasoline injection represented the optimum of what could be reached with this engine concept. The multi-rotor design called for peripheral ports for the intake-air and exhaust-gas ducts. We were able to solve the difficult problems in engine cooling and engine mechanics by technical means. But the concept’s main problem – its low thermodynamic degree of efficiency – persisted.”

At just 1.12 metres in height, a number of details about this flat sports coupé made reference to the history of Mercedes-Benz supersports cars. Such features included the gullwing doors, reminiscent of the 300 SL, and the consistent use of innovative drive technology in a high-performance automobile. Unlike the 300 SL (spaceframe with steel and aluminium skin), however, the C 111 had a body made of glass fibre reinforced plastic, which was bonded to the steel floor assembly.

Ultimately, the reason the C 111-II became such an object of desire among the public – in spite of being officially presented as a study and experimental vehicle – was down to the high standards Mercedes-Benz set itself. For during its development, the sports car was never treated merely as a test vehicle. Rather, the engineers looked beyond the innovative drive and body features, applying themselves to the vehicle setup and creating a holistic concept that also embraced design of the interior, noise insulation and chassis optimisation. When the C 111-II appeared at the 1970 Geneva Motor Show, it inspired the feeling of a supersports that had been built as an integrated whole – an automotive dream that was close enough to touch.

\n

\n

\n

\n

\n

\n

\n

\n

\n

\n

\n

\n

\n

\n

\n

\n

\n

\n

\n

\n

\n

\n

\n

\n

\n

\n